Version control: Git and Github

Learning goals

The goal is that after this week, the student will

- Understand the motivations for using version control.

- Know how to create a Git project.

- Understand what a commit is and knows how to create one.

- Understand the different states a change goes through before it’s added to a commit.

- Understand what the master branch is.

- Know how to read the output of the command

git status - Know how to create a repository on GitHub and add it to an existing Git project.

- Know how to use GitHub through an SSH connection.

- Know how to publish locally made commits.

- Know how set locally made changes aside to the stash, and how to get them back.

- Know what a merge commit is.

- Know what a merge conflict is.

- Understand how a merge conflict is formed.

- Know how to solve a merge conflict.

- Know how to view old commits on GitHub and the command line, and how to move back to the latest commit of master after checking out old ones.

- Know how to clone a Git project to their local machine.

- Understand how GitHub can be used in team projects.

- Know what an issue is.

- Know what forking a project means.

- Know what a pull request is.

Version control: Git and GitHub

This part of the course handles version control. Version control refers to a service used for storing code. There are two primary reasons for using it: Version control allows storing backups of both the current and older versions of a program. In addition, code and projects can easily be shared with others, which makes collaboration easy.

Version control tools allow marking a specific state of a project as so that one can return to it later. Thus, if something goes wrong in the development of new features, one can return to an older and functional version of the project. Version control stores all the marked states. Therefore all the developers can follow the evolution of the program, like who has done what and when. This also makes finding bugs, or errors in the program, a lot easier.

Contrary to what many people think, programming is mostly done in groups. With version control tools it is possible to use and develop others’ code, even without ever meeting in person. People can give verbal feedback, such as report issues, as well as make concrete suggestions for improvement by providing code to the project. All developers are kept up to date about the state of the project, which makes cooperation smoother.

Visul Studio has summarized reasons for using version control on their website. Bitbucket has also written a longer text about version control.

There are several different version control tools available, but this part will focus on using Git and Github, especially in the context of programming projects.

About Git

Git was initiated by Linus Torvalds, the original creator of Linux. Torvalds is most likely more famous for being the primary developer of the Linux kernel, which is the “heart” of many operating systems, such as Google’s Android.

Torvalds started developing Git for his own needs when coding the Linux kernel. He needed a tool for storing different versions of his own code and sharing it with other people.

GitHub is a service which was created later on, used for storing and publishing projects. There are several sites similiar to GitHub, such as GitLab, however, this part deals with using GitHub as it is more popular and mature.

Git and GitHub are used in solo as well as collaborative projects at University and in the industry. It’s usage isn’t limited only to code, and many people like to for example backup their thesis using Git. Nevertheless, this part focuses on sharing code with GitHub, and some of the common problems faced in the process. Git will certainly be useful in your studies, and you will learn more about it in the software engineering courses.

Exercise 1: Creating a GitHub account

Start by creating a GitHub account at https://github.com/ . Programmers often use GitHub as a sort of code protfolio, so make sure to choose a username which you don’t mind adding to your CV.

If you already have a GitHub account, consider this exercise done, and use the one you have.

Git should be already installed on the schools’s computers. We’ll learn how to use the command line client of Git.

Exercise 2: Configuring Git

Let’s configure Git a bit.

Link your name and email address to Git so that all the changes you make to different projects are properly associated with you. This can be done by running the following commands with your own personal details:

git config --global user.name "My Name"

git config --global user.email email@address.com

If you don’t want your email to be public, GitHub offers a specific noreply email.

Make sure you noticed the “Note” part on the site linked above! The form of the noreply email depends on when you created your user. If you created an account only on this course, you can have a no-reply email only after setting your email as private from your account’s settings.

If you’re not accustomed to using Vim, change the default editor of Git to nano with the following command:

git config --global core.editor nano

In Windows replace nano with notepad.

Starting a Git project

A project is simply a directory containing some files. These files can for example have code in them. You can turn a directory into a Git project by running the command git init inside it. This will allow running git commands inside the folder. The initialization command will create a subfolder called .git. This folder stores all sorts of information about the project in the directory it is located in.

Commits

Information is stored to Git with commits. A commit is a bundle of changes which have been made into files inside the project. In practice these changes are often adding or removing text from a file, for example.

You can think of a commit as a step towards a finished project. Every commit adds some changes to the previous commit. For example, when developing a program, it would be natural to add a new feature in a new commit.

Let’s go through how a commit is created. First, the changes one wants to include in the commit are added to the staging state. When all the desired changes are in staging, the commit is wrapped together, sealing all the changes together.

The command git status will turn out to be very useful in the process of creating commits, as it gives information avout the current state of the project and all the files inside it.

Let’s create a Git project folder, and add an empty file called tools.txt inside. You can do this with the command touch for example. When a new file is added to a fresh Git project, git status will print the following:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

tools.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Next we’ll take a closer look on the output of git status.

The different states of changes

Changes can be added to the next commit by running git add. The command requires one argument, that is the path to the file containing the changes one wishes to move to staging and consequently include in the next commit. Before a file has been added to Git, it is under Untracked files. This also means that the changes inside that file will not be added to the next commit.

Now let’s add the changes in the file we created earler by running git add tools.txt. Then we’ll insert some text into the file with echo “this is the second part of tools” » tools.txt. Then we’ll run git status:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: tools.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: tools.txt

Next we’ll add one more file to the project, called empty.txt. We’ll then run git status again, which outputs the following:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: tools.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: tools.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

empty.txt

Now let’s break down the output.

The first title is called Changes to be committed. The changes under this title will be added to the next commit.

Changes not staged for commit refers to the changes which Git is aware of, which will not be added to the next commit.

Finally Untracked files contains all the files which are unknown to Git, meaning that the changes inside them are not being followed. For example, Git cannot distinguish what sort of changes have been done to the untracked files. In consequence, the changes are not being added to the next commit.

You probably noticed that the file tools is in the output twice. This is because Git tracks changes. The first change added to Git was where the file tools was created. Only after adding the change to Git was some text insterted into the file. Thus only the change where the file tools was created will be added to the next commit, and not the change when some text was added inside it. The interpretation of the output of git status is made easier with some colors. The changes which will be added to the next commit are displayed in green, and next to the filename is written what was done to the file (for example new file, modified, deleted).

Changes can also be cancelled with Git. Adding some text to tools.txt could be cancelled by running git checkout – tools.txt. The file will be empty after running the command because the command cancelled the change which added some text into tools.txt. In conclusion, the command git checkout – enables cancelling changes in tracked files.

By running git add -p one can choose change by change, which ones to add to the next commit (y=add, n=don’t add). The command only takes into consideration changes in files which are being tracked, i.e. have already been added to Git once. Thus new files cannot be added to Git with git add -p. Running git add file will add all the changes in the file. It is also possible to add entire folders to Git using the same command.

NOTICE! If you think there is a possibility that you will want to share a project with other people some day, don’t add anything secret to Git. Even if you remove the secret content in the next commit, the delicate information stays in the project’s history, and can be found from GitHub easily.

A good habit to form is to constantly check which changes will be added to the next commit with git status. This might save you a lot of trouble later on.

Creating a commit

After choosing which changes will be included in the next commit, you can finally create the commit with the command git commit. Every commit has a message attached to it, describing the changes included in the commit. The message is added upon creating the commit by running: git commit -m “a descriptive message”, where your descriptive message specifies what has changed since the last commit. If you leave out the flag -m and the message, a text editor will open, where you can write a longer, detailed description below the title message. The commit is then created by saving and exiting the text editor.

Here are some quick instructions about writing a good commit message.

We’ll continue where the previous example left off. Let’s add all the changes we made to the next commit, except the creation of the file empty.txt. Before running git commit, the output of git status is:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: tools.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

empty.txt

Then we’ll run git commit -m “Add new tools file”

Now the output of git status is:

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

empty.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

The changes which were commited are no longer visible in the output. However, they are not lost, they have just been moved to the commit. You can view the commits of a project with the command git log:

commit 51bf544c786a671c28f70713b6cb33d87cc38

Author:

Date:

Add new tools file

The command git log outputs the author of the commit, the time of its creation and its title. Every commit has a unique id, formed with SHA-1. In the output of git log the id can be seen as a long string next to the word “commit”, which is 51bf544c786a671c28f70713b6cb33d87cc38 in this case.

The process of creating a commit might seem unintuitive at first. The following analogy might help: Picture the commit as a package. You are sitting on the floor, with all the changes layed out in front of you as wooden blocks. The staging state, denoted with the title Changes to be commited is a piece of wrapping paper, which is spread out in front of you. With the command git add you can move the wooden blocks representing changes on top of the wrapping paper, and with git commit you tie the wrapper aroung the changes to create a commit.

Branches

At the top of of the output of git status, you can see the following text: On branch master. Branches allow separating some commits from others. This means that a new branch can be developed independently from an old branch. It is customary for projects to have a main branch, usually called the master branch, containing the version currently in use.

Branches are usually used for testing out new features without breaking a working version of the program. Since branches don’t affect each other states, the new branch can be played with without worrying about other ones. When the changes made to the new branch are deemed ready, the branch can be merged to the master branch, and thus the new features will be published. Although branches are an important part of Git, this course will not focus on using them. It suffices to understand that we will only use the master branch in the exercises and in the exam.

Exercise 3: Practising working with commits

- Create a folder on the command line and turn it into a Git project.

- Create a file called “story.txt” in your project. Add a lot of text inside.

- Add another file called “shopping_list.txt” to the project, and write down what you need from the store (or just many rows of text).

- Create a subfolder called “school” into the project, and create a file called “tools.txt” inside. You will need these files in the future exercises.

- After doing all the changes described above, create a total of three commits: one, where you add the story, a second on where you add the shopping list, and a third one where you add the school folder. Make sure that each commit message is truly descriptive.

- Using the command “git log”, check that you have properly created three commits.

- Add something new to the shopping list, and create another commit. Use the command “git add -p”.

- Make sure you can see all the commits in the output of “git log”.

If you see the following message when creating a commit error: cannot run : No such file or directory error: unable to start editor, make sure you configured the default text editor of Git properly (go back to exercise 2).

Exercise 4: Removing changes

- Find out how you can remove changes from the state where they are being added to the next commit (under “Changes to be commited”), and move them under the headline “Changes not staged for commit”? Hint: git status will help.

- Add some new products to the shopping list, and add them to the next commit (so that they are under Changes to be commited). Don’t create the commit yet.

- Then remove the changes from the next commit.

- Then remove the changes, using Git, so that when you open the shopping list, the new products are not there.

Sharing code via GitHub

Next we’ll learn how GitHub can be used alongside Git for sharing and publishing code.

Creating a remote repository

In order to share a project through GitHub, a repository (or simply a repo) has to be created for it, and it has to be linked to a local Git project. After a remote repository has been added to a project, information can be shared between them. In consequence, two concurrent versions of the project will exist: the remote in GitHub and a local version on a specific computer.

This shows how GitHub functions as a backup storage. When the state of a project is updated to its remote in GitHub, it can be accessed from anywhere with internet. Thus the project can be continued even if its local version is destroyed or damaged.

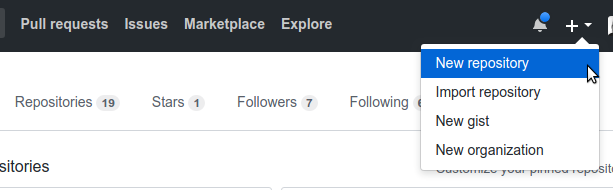

You can create a repository to GitHub by pressing the button on the upper right corner:

A window will open where you can add the repository a name and a description. A repository can be public or private: a public repository can be accessed by anyone, whereas a private repository can only be seen by people chosen by the owner.

You can also create a README, a license and a .gitignore file when creating a repository. The point of a README file is to display useful information about the project. A good README contains, for example, a short description of the project, installing instructions and a link to the documentation. A license refers to a document stating the responsabilities and rights of the creator and the users of the project. The .gitignore file allows automatically ignoring some files when creating a commit, and it is often quite useful. You can read more about it here.

When you wish to update a pre-existing project to GitHub, it is not a good idea to let GitHub create files such as a README automatically. This will lead to problems, because GiHub contains files initially which are not found in the local project. You’ll learn more about these kinds of situations later in this part.

The button Create repository adds the project to your personal account. When you navigate to the empty project, you can see some useful instructions about adding a new project to tour profile. You can find all your projects from your profile, or navigate to them directly with https://www.github.com/username/projectname.

Adding a remote

A remote can be linked to a local project with the command git remote add.

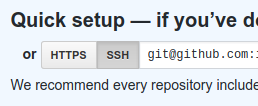

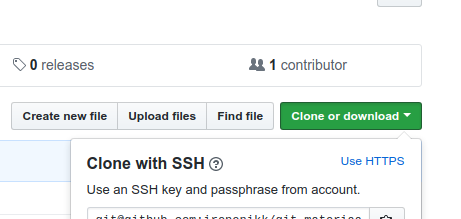

The command takes the name and the address of the remote repository as arguments. GitHub offers two options for the repository address protocol: SSH and HTTPS. SSH of connection is possible to use also with GitHub, if the local system has an SSH key pair, and the public key has been added to GitHub. If the user uses the HTTPS connection type, they will be authenticated with their GitHub username and password. Using an SSH connection is therefore a little less tedious, since the private key can be added to the ssh-agent.

We’ll choose the SSH address for the remote project:

A new repository called “origin” is added using an SSH connection by running the command git remote add origin git@github.com:user/project.git. An HTTPS address would be almost identical to the URL in your browser. A remote can be called practically anything besides “origin”, but it is a good and a common choice. It is possible to add several remotes, when properly naming them becomes important.

Exercise 5: SSH key to GitHub

If you haven't created an SSH key pair on your computer, do it first. The instructions can be found from GitHub documentation.

Add your public SSH key to your GitHub account. GitHub has instructions for it.

If you don’t want to install a new program (as suggested by the instructions), you can print the SSH key to your terminal with the command cat, copy it by hand, and continue following GitHub’s instructions from step 2.

Exercise 6: Creating a remote in GitHub

Create a remote repository for the project you created locally.

Don't let GitHub create a README, license or a .gitignore file when creating the repository. Doing so will cause problems later.

Add the repository as a remote to your project. If you did the previous exercise, use an SSH address, otherwise use HTTPS.

NOTICE! Here you will get the repository address! You can find it in your browser address bar, and it is in format https://github.com/username/repository, where username is your GitHub username, and repository is the name of the repository you have just created.

Publishing

After a project has been added to a repository in GitHub, commits can be published by pushing them to the remote repository.

Changes can be pushed to a specific branch in the remote repository as follows: git push remotename branchname. In this part we will only use the master branch. If you add the flag -u after the command push, next time you do not need to specify the name of the remote and the branch to push changes to the same place. Using the flag -u is recommended.

Let’s push the changes we made to the file tools.txt by running git push -u origin master, since we named the remote origin and we are using the master branch. Next we’ll navigate to the project site on GitHub. There we will find the file tools.txt.

Exercise 7: Publishing a commit

- Push the three commits you made earlier to the master branch of the remote repository.

- Check on GitHub that you can find all the changes in the remote.

Fetching code from GitHub

There now exists two versions of the project: one locally, and one in the remote at GitHub. Let’s see what happens, when these two versions don’t stay properly synced.

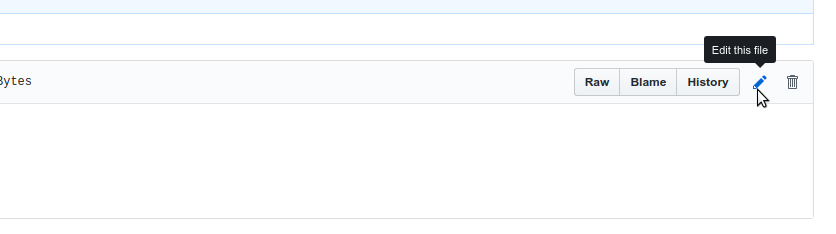

We’ll start by making changes to the project via GitHub. You can edit files via GitHub by clicking on their name and then clicking on the pen icon on the right side of the page.

Next we’ll add a new line of text to tools.txt, and create a commit of the change using the green button at the bottom of the page. However, you can’t see these changes locally.

We’ll run the following commands:

git fetch

git status

The command git fetch fetches the newest state of the project from GitHub, but doesn’t change the local version. If you find that git status doesn’t show up-to-date information about the state of the remote, you should run git fetch first.

We still can’t see the new line of text locally. However, if you pushed with the flag -u, Git will notice that the remote repository contains some changes it doesn’t see locally: Your branch is behind ‘origin/master’is printed at the top of the status output.

You can get the new changes to the local version by running git pull. If you used the flag -u with push earlier, there is no need to specify a remote or a branch. We’ll run git pull, which results in an output along the lines of the following:

remote: Counting objects: 3, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

From github.com

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

8793615..c661629 master -> origin/master

Updating 8793615..c661629

Fast-forward

tools.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Now you can find the new line of text in the file you changed via GitHub.

Exercise 8: Fetching code from GitHub

Create a new file to the school subfolder via GitHub, and fetch it to your local version.

In practice the situation handled above corresponds to working on a collaborative project, where someone else has added commits to the project and pushed them to GitHub. Other developers should then fetch the new changes with the command git pull.

Stash

Next we’ll find out what happens, if GitHub contains some information not found in the local version, and vice versa.

Let’s change the first row of tools.txt via GitHub. This will create a new commit to the remote version. Then let’s add a new line at the end of the same file in the local version, but without creating a new commit of the new change.

Now if we try to fetch the latest changes with the command git pull we’ll get:

From github.com:

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Updating 061ca96..6920cd0

error: Your local changes to the following files would be overwritten by merge:

tools.txt

Please, commit your changes or stash them before you can merge.

Aborting

Pulling the new commit from the remote does not work, because the local verison holds changes to the same file as the remote repository, and the local changes have not been wrapped into a commit.

In situations like this one can put the local changes aside to the stash. This is done with the command git stash. When the command is run, the local changes in files tracked by Git will by hidden, but not lost completely. In order to also stash changes in untracked files, add the flag -u. Changes can be returned from the stash by running git stash pop.

Exercise 9: Using stash when pulling from the remote

- Make changes to some files which you have already added to Git once (i.e. they are not under the headline UNTRACKED in the output of git status).

- Stash the changes you just made using Git.

- Open the files you last and check if you can still see the changes

- Edit the first sentence of the file story.txt in GitHub and create a commit.

- Then edit the last sentence of the same file locally, but don’t create a commit.

- Fetch the changes you made to story.txt in the remote repository to the local version. Use the stash.

- After you have successfully fetched the changes to the local version, create a commit of the changes you made to the last sentence of story.txt.

- Push the end result to GitHub.

- Make sure you can see both the changes you made to the first sentence and the ones to the last sentence in the remote version.

If you see “CONFLICT” outputted to the terminal when popping changes from the stash, the section “Merge Conflicts” will help.

Merge

We’ll continue working with two parallel states, as they are probably the biggest stumbling block for new users of Git.

In the previous example, the remote and local versions had different states, because both contained infromation which the other did not have. Because local changes hadn’t been commited, they could be put aside to the stash. What would have happened if the local changes had been commited, i.e. the remote repository and the local project had commits which the other one doesn’t have?

The situation can be solved by merging together the commit in the remote version and the commit in the local version. Merging simply means combining parallel states. If the two states do not conflict, meaning that they do not contain changes overriding each other, Git can merge them automatically. A new commit, called a merge commit, is created in the process.

Actually, merging is built into the command git pull. In other words, it suffices to run git pull in order to combine the state of the remote to the state of the local version. In order to finish the automatic merge, the merge commit has to be given a message. Thus when you run git pull, a text editor will open, where Git has added a suggestion for the commit message. You can edit this message as you please, and create the commit by saving the message and exiting the editor, which concludes the merge.

Let’s test merging in practice. We’ll start by creating two non-conflicting commits by creating two new files, one in the remote repository and the other in the local version. After creating the two commits, running git status will output:

On branch master

Your branch and 'origin/master' have diverged,

and have 1 and 1 different commit each, respectively.

(use "git pull" to merge the remote branch into yours)

nothing to commit, working directory clean

Notice how Git is kind enough to notify us of the two parallel, differing states, and it even advices us on how to proceed.

Remember that if git status doesn’t display the newest state of the remote, you shoud run git fetch first.

Pushing the now commits will not work, as the command git push will output the following:

To git@github.com:user/repo.git

! [rejected] master -> master (non-fast-forward)

error: failed to push some refs to 'git@github.com:user/repo.git'

hint: Updates were rejected because the tip of your current branch is behind

hint: its remote counterpart. Integrate the remote changes (e.g.

hint: 'git pull ...') before pushing again.

hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details.

However, Git gives instructions on what to do next. We’ll fetch the new state of the remote and combine it with the local version by running git pull. When a text editor opens, we’ll give the merge commit a message, save it, and exit. The following will be printed out to the terminal:

From github.com:user/repo

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

new_file.txt | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 new_file.txt

Now according to the output of git status we have created two commits, (ahead by 2 commits). The first one is the commit we created locally, which added one new file to the project, and the other one is the merge conflict. Pushing the two commits to GitHub should not result in any errors.

Exercise 10: Merging

- Create two non-conflicting commits, one directly to the remote repository, and another to the local version. For example, edit the first line of your shopping list via GitHub, and the last line on the local version.

- Try pushing the local commit to the remote repository and observer the error message.

- Pull the commit from the remote repository to your local version and write “my first merge” as the commit message.

If you see “CONFLICT” printed out while pulling, read the next section “Merge Conflicts”.

- Finally, push all the changes to GitHub.

Merge Conflicts

When several people are working on the same project, it is not uncommon for two developers to make changes to the same lines in some file. When merging the two changes together, how does Git know which of the changes to discard and which one to keep? Well, it doesn’t, and so when mutually exclusive changes are found when merging, the automatic merge will fail. The conflict between two commits (or branches) is called a merge conflict. In these cases, someone has to hand pick the changes which will be kept in the project. This is called resolving a merge conflict.

Next we’ll create a merge conflict. We’ll start by writing “Greetings from GitHub” to a line in the tools.txt file via GitHub, and finish off by creating a commit. Then we’ll edit the exact same line locally by replacing it with “Greetings from my computer”, and wrap the change up to another commit.

Now when we try to combine the newest states from the remote and local versions together with git pull, we get the following error message:

Auto-merging ...

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in tools.txt

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

This means that we have successfully created a merge conflict. The line starting with CONFLICT tells us where the overlapping changes can be found. Let’s open the file in question, tools.txt. We see the following:

<<<<<< HEAD

Greetings from my computer

======

Greetings from GitHub

>>>>>> baaf2c96cw031e11138d42c1a35065b9bf8b4400b

The mutually exclusive changes are separated with the symbols <, > and =. The word “HEAD” refers to the current commit (or the latest commit of the current branch in the local version), and the long letter and number combination is the id of the conflicting commit, coming in from the remote version. Advanced editors such as Visual Studio Code enable resolving conflicts with just a simple click, but otherwise the only option is to simply remove the lines one doesn’t wish to keep in the project.

Notably, we’ll remove the lines starting with <, > and =. In addition, we could for example combine the two greetings into one. In essence, the person resolving the conflict decides what remains in the file where the conflict is located.

In this case, we’ll combine the greetings into a more concise one:

Greetings from my computer and from GitHub

Now running git status will output a message reminding us that we are currently resolving a merge conflict:

On branch master

Your branch and 'origin/master' have diverged,

and have 1 and 1 different commit each, respectively.

(use "git pull" to merge the remote branch into yours)

You have unmerged paths.

(fix conflicts and run "git commit")

Unmerged paths:

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: tools.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Let’s add the resolved file to Git with git add (note that the flag -p would not work in this particular case). Running git status will then yield:

On branch master

All conflicts fixed but you are still merging.

(use "git commit" to conclude merge)

Changes to be committed:

modified: tools.txt

Finally, we’ll wrap up resolving the conflicts by, you guessed it, creating a new commit. The finishing touch is to push the result to GitHub, so that other developers can use the newest version.

Merge conflicts are enfuriating, but rather common when collaborating with others. The easiest way to avoid them is by making sure to always start developing on the newest version from the remote, i.e. by pulling before starting development. However, sometimes they cannot be avoided, in which case one must patiently go through the conflicting files.

Merge conflicts can also occur when taking changes out of the stash, if the hidden changes overlap with new ones.

Exercise 11: A Merge Conflict

Create a merge conflict in your project and resolve it. Make sure to push the end result to GitHub.

Commit history

All the commits added to a Git project add up to its commit history. Commit history is like a chain of commits, formed when commits are created on top of each other.

Storing a project’s commit history is one of the greatest benefits of using version control. It allows returning back in time to a working version of the program, or observing how certaing files and features have changed over time.

Examining commit history

GitHub provides arguably the easiest tool to examine a project’s commit history. We’ll start revisiting our project’s commits from there.

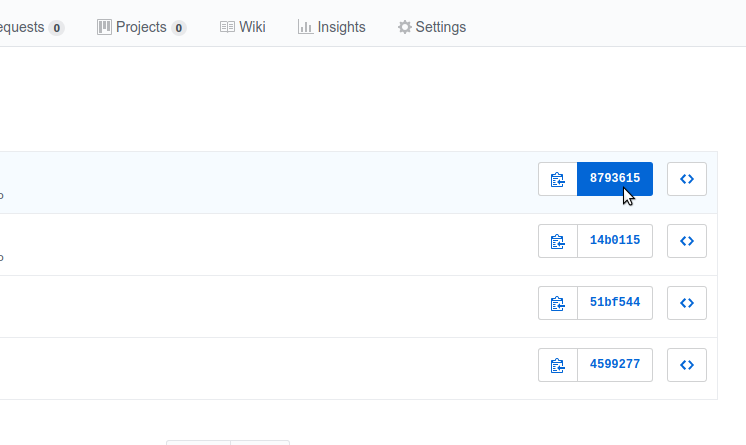

Let’s navigate to our project’s front page. At approximately the center of the page you should see a bar, whose upper left corner has a tab allowing you to view the old commits. Here the tab says “4 commits”.

When you click on the tab, you’ll see a list of all the commits which have been added to the project. There are three buttons on the right side of this view.

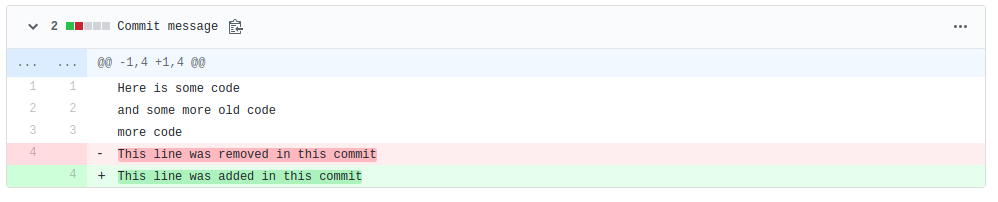

The button at the center of those three shows the beginning of a given commit’s id. Pressing the button shows all the changes made in that particular commit. The additions are shown in green, and removed lines in red.

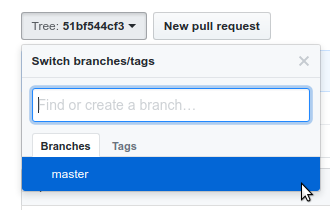

Then by pressing “Browse files”, or the rightmost button with <> written on it from the previous view, you can browse the state of the project after a specific commit. A commit only contains a set of changes, but Git still enables revisiting the whole project after a given commit. You can return back to the latest commit of the master branch by pressing the “tree” button on the left, and by choosing “master”.

Of course, the same procedure can be repeated on the command line. You can browse the state of the project after a specific commit by running git checkout commit_id. You should check the id using git log for example. Similarly, you can move back to a specific branch by running git checkout branch_name, most commonly git checkout master. The changes made in a specific commit can be viewed with git show commit_id.

Exercise 12: A Secret

- Create a new file to you project called “secret.txt”, and write something inside such as “this is a very important secret”.

- Create a new commit of the new file and the contents added to it.

- Then remove the file secret.txt, and create a new commit of the deletition.

- Push the changes to GitHub.

- Navigate to the project page on GitHub. You shouldn’t see the secret on the front page. Find the secret from your commit history. Find the secret also using the command line.

Remember, don’t push anything secret to the remote repository: no passwords, personal API keys, your student number, or anything you wouldn’t want to share with the whole Internet.

GitHub’s workflow

Sites like GitHub make collaboraton in development projects a lot easier. No one notices problems more efficiently than the actual users, and GitHub creates a platform for reporting those complications. Any user can create an issue to a public project in GitHub, where one can report any problems with regards to using the software. Common issue subjects are error messages in edge cases, problems in installing, or missing features.

If one knows the solution to a problem, they can even suggest their own improvements to the project. However, this requires having access to the source code of the project. A public project can be copied to a local computer with the command git clone. The command takes the address of the remote repository, which can be acquired from the upper right corner of the project page, as an argument.

Note that this is actually the same address you used before when adding a remote repository with the command git remote add. The owner of a project will not know who has cloned their project.

In the future, when you start a new Git project, you have two options for linking the local project to a repostory in GitHub. One option is to start by running git init inside a folder, create a repository to it in GitHub, and link them together. Another possibility is to create the remote first and simply clone the empty project to your local machine.

In order to push some new commits to a project one has cloned, the project’s owner has to add the user as a collaborator. Otherwise the command git push will fail, because the user doesn’t have sufficient permissions to the repository. In other words, when starting a collaborative project, all the developers should be added as collaborators, allowing them to push code to the remote repository freely.

However, there exists another way of suggesting changes to an existing project. This is called forking. When one forks a project, a copy of it is added to the users own profile. This will create an event to GitHub’s “feed”, and the project’s owner can see who has forked their repository. After forking a project, you can clone the project from your own profile, and push changes to your own version, which has been separated from the original one. The difference to cloning is, that the cloned repository will not appear in your GitHub profile.

If the chages you have done to your own version are good enough in your own opinion, you can suggest merging them to the original project with a pull request. The owner of the original project can then go through your suggested changes and to integrate them to the project if they wish.

Exercise 13: Cloning

- Find out using Google, how you can find out the names and addresses of the remote repositories of a project. The answer is a command you should run inside the Git project, when a remote has been set

- Find an open source project of your choice from GitHub (you can for example check our course materials from Centria’s GitHub for some projects). First clone the project to your local machine. Then find out what the name of the remote repository is set to by default. You can do this with the command you found in the previous part of this exercise.

Exercise 14: Exploring a project

Explore an open source project in GitHub. Find the issues and the pull requests, the people who have contributed to the project, and the statistics associated with them.

The End

As a novice programmer it is easy to lose and even break code with version control. However, learning how to use one is definitely one of the most vital skills required in the working life. Though the system in use may not be Git, the same principles often apply.

If you run into a strange error message, don’t be afraid to ask for help. Avoid running commands blindly. Keeping a close eye on the output of git status will get you a long way. Also remember to make commits a sensible size, push them to the remote repository regularly, and communicate with your team mates. The best way to learn how to use Git is to just do it, so don’t give up and remove the project upon the first error message. Remember, that you can always just clone the repository to your computer again.

Now congratulate yourself, rest for a bit and take a break before returning to check the learning goals.

Hungry for more? You can read about Git from the following sources:

- https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2

- Pro Git Book is rather heavy, but a comprehensive guide to using Git. It might be best to use as a reference for specific problems. Reading it from cover to cover might be unnecessarily cumbersome.

- http://ohshitgit.com/

- A fun way of getting help to most common Git problems.

- Some commands include overwriting Git history, which was not covered in this part. This might cause more problems than it helps. However, the site may be helpful in desperate times. Especially the first command git reflog can get you out of many complicated situations.

- https://try.github.io/

- A tutorial by GitHub, starting from the basics. Handles some things which are not covered here, like git diff.

- If you’ve already gotten to know Git, you might be interested in learning more about its history. Storing commit history, demonstrated in the exercise “A Secret”, also enables overwriting history. Although this can be useful for covering up mistakes, rewriting history can be dangerous in collaborative projects, since it can make other people’s versions invalid. There is a tutorial on the subject by Atlassan. They also have other advanced tutorials.